Book reviews

(first published in Habibi, volume 15, number 3, summer 1996)

Irangeles, Ron Kelley and Jonathan Friedlander, editors. University of California Press, 1993.

An Introduction to Iranian Culture, Shahnaz Moslehi. Eqbal Printing and Publishing, revised edition, 1994.

A few years ago my husband’s Aunt Marion came to tea with her friend Mrs. Cohn, who lived in Beverly Hills. The conversation turned to Iranians in Los Angeles, at which point Mrs. Cohn told us that there were many Iranians at her synagogue, but that, although the women had assimilated just fine, the men hadn’t assimilated at all. I asked what she meant, and she replied, “Oh, they always come to services in their native dress.” My mind began to reel with visions of turbaned Kurds in baggy pants, mustachioed Baluchis with their long overshirts and carbines strapped around their chests. What exactly did she mean by native dress, we asked. She replied “Beige and white silk suits.”

If you have encountered Iranian émigrés in the United States, you may have noticed that while they do not wear a special dress — as the Saudis, for example, do — they can easily be distinguished by a certain difference in style from the average middle class urban American. Their customs, traditions, notions of male-female relationships, and notions of “western” dress are different from ours. The two books reviewed herein attempt to explain these differences, and to help non-Iranians in the United States understand Iranian culture — both the version in Iran, and the version among the exile community in the United States.

Irangeles is a collections of essays, photos, and interviews with Iranians in Los Angeles, on a variety of topics including the ethnic and religious sub-groups, occupations, male-female relationships within the new culture, politics, and popular culture. It begins with an excellent short overview of 20th-century Iranian history by Mehrdad Amanat, as a background for why there are so many Iranians in Los Angeles, when they immigrated, and how. The book then discusses the primary Iranian ethno-religious sub-groups in Los Angeles: Muslims, Jews, Armenian Christians, Assyrian (Nestorian) Christians, Zoroastrians, and Kurds.

The topic of American attitudes towards Iranian immigrants, particularly during the “hostage crisis” of the late 1970s, is presented with an eye towards providing some understanding of the Iranian experience during this period. It is of course a great irony that during the hostage crisis American zealots were publicly castigating Iranian immigrants, the very people who had the most to fear or had suffered the most from the Iranian Islamic regime. These were the ones who had escaped, often at great personal risk, in order to escape even greater risk and suffering at home. Interviews with a young Jewish woman who escaped via Pakistan, and with “Maryam”, who was imprisoned and tortured by the Khomeini regime, remind us of exactly why there are so many Iranians here.

The book began as a photography project, and includes 159 photographs of the Iranian community in Los Angeles. While the photos are not great works of art, there is much in them that illustrates the points made in the text, and would be of interest to the reader seeking information about the community. A warning: several grim and heart-rending photos depict the self-immolation suicide of Neusha Farrahi, in protest against the Islamic Republic, pro-Shah royalists, and United States foreign policy.

Though dance is rarely mentioned, dance photos include a woman dancing on a table at a Now Ruz (Persian New Year) concert, Zoroastrian girls doing a traditional dance for Mehregan (harvest festival), girls in an Armenian dance class, Jewish children at a Hanukkah dance, a young woman dressed in an “I-dream-of-Jeannie” costume for a Halloween party, a woman dressed in a cabaret belly-dance costume at a Halloween event, and a couple dancing in the traditional Tehrani couple style.

Photos of cultural activities include weddings of all faiths, promenading in Palisades Park on Sunday afternoons, Sizdah Bidar (thirteenth day of the Persian New Year, spent outdoors) picnicking, Now Ruzhaft seen (seven S’s) display, and fire-jumping at Chehar Shanbe Suri (last Wednesday before Now Ruz).

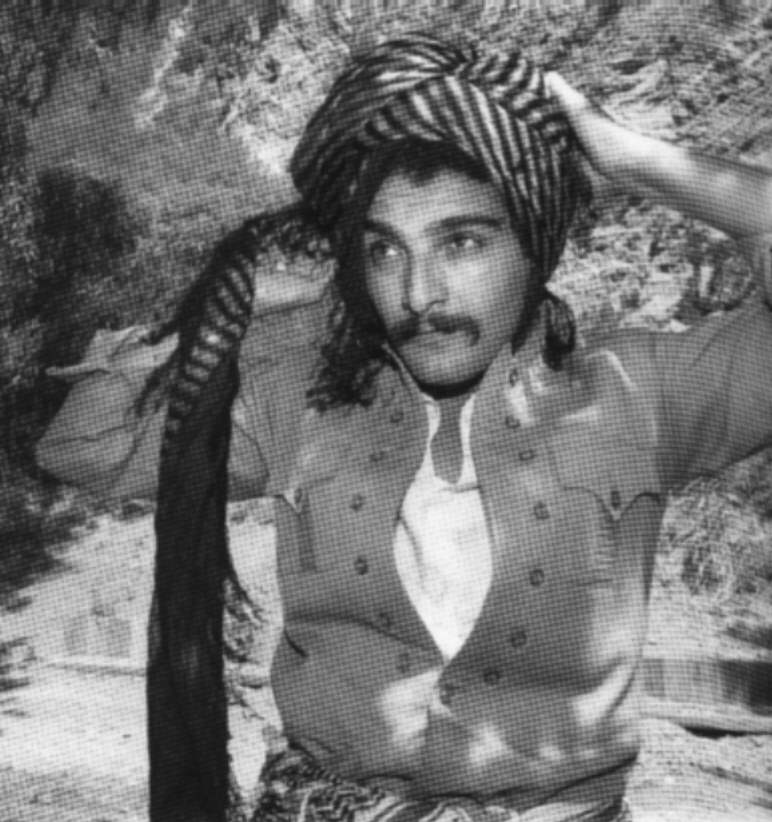

My personal favorites among the photos are number 58, a young Kurd wrapping his turban, number 81, a young woman playfully wearing grass from the haft seen on her head, and number 97, a woman in a white dress with black polka dots and her Dalmatian puppy.

The authors, being scholars, take a scholarly approach to many of the topics. Only in one essay, however, does this approach become disappointingly opaque and academic: the essay on popular culture by Hamid Naficy. This essay is largely a catalog of cultural factors without much synthesis, full of ponderous statements like the following: “In this symbiotic process, popular culture both furthers assimilation and sustains alternative values that can be a source of vitality for the mainstream culture as well as the ethnic subcultures”.

Most disappointing to me personally as a dancer and musician is the complete absence of any mention of the Persian traditional music scene in Los Angeles, and no mention of any of the fine performers, both residents and visitors, who provide an alternative to western-style Iranian “pop music”, despite the fact that several of these traditional performers are depicted in the book’s photographs. The efforts of Hossein Alizadeh (tar, setar, and robab), Mohammad Reza Lotfi (tar and setar), and Morteza Varzi (kemanche), and a host of others, to preserve traditional Iranian music in the face of overwhelming western influence should not go unmarked. Also virtually undiscussed are the fine dancers and dance companies in Los Angeles:

Sabah Dance Company (directed by Mohammad Khordadian), Pars National Ballet (directed by A. Nazemi), Nay-Nava (directed by Shida Pegahi), and Jamile. No mention is made of either of Los Angeles’ two large international folk dance troupes — Anthony Shay’s Avaz Dance Theater which, though directed by an American, has been catering to Iranian tastes since 1977, or the AMAN Folk Ensemble, founded by Shay and Leona Wood in the early 1960’s, which has been presenting Iranian music and dance periodically since that time, including at the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival.

Despite these lapses, I believe that Habibi readers will find this book of great interest as an introduction to Iranian culture in exile.

In An Introduction to Iranian Culture Dr. Shahnaz Moslehi takes a more personal approach, presenting Iranian history and culture with the goal of acquainting non-Iranians with what they might expect in a relationship with an Iranian. This little book contains a wealth of information for the newcomer to things Iranian, including Iranian history, geography, philosophy, culture, and social habits.

The author gives a concise description of city and village life in Iran in the twentieth century, as well as a brief history of the Iranian people, starting from 1,000 B.C.E. She uses the latter as a basis for a description of the Iranian national character, and shows how modern Iranian psychology relates to the Iranian national past.

Dr. Moslehi describes the various religions practiced in Iran, summarizing their historical developments and the status of their practitioners in Iran. The descriptions of Iranian holidays, various common occupations, and other cultural information are most interesting and informative.

The book includes helpful hints on how to relate to Iranians, especially potential future in-laws. The appendix of phrases in Farsi could also be useful, not only in dealing with potential future family members, but also in communications with Iranians one might meet in the apartment building, at work, etc.

This little book, rich in useful information as it is, is not without its flaws. Much of the information on the pre-Islamic history of Iran is taken from A History of Iran for Youngsters (Washington, D.C.: Foundation for Iranian Studies, 1983; written in Farsi), and is much simplified and full of historical errors. For example, on page 46 Dr. Moslehi says that “the Aryans…moved from their original homeland in Mid-Europe to Mesopotamia.” Not so: The original homeland of the Indo-Europeans (of which the Indo-Iranian, or Aryan, tribes were a part) is believed to have been the Eurasian plains of southern Russia, from which the Aryans traveled south, passing through both the Caucasus and Transoxiana (to the west and east of the Caspian) to the Iranian plateau and the Indian sub-continent, respectively [Iran, R. Ghirshman, 1954 edition, Great Britain].

Other problems include Dr. Moslehi’s transcriptions of Farsi phrases, which she has transcribed in the style of the formal written language, but no one actually speaks that way. These phrases could be spoken as written, but it would be obvious to any Farsi-speaker that the phrases had been learned from a book. In addition, her inconsistencies in transliterating the vowels and consonants of Farsi would leave the inexperienced with no way to produce the sounds accurately enough to be understood.

These flaws are a pity, as the book is otherwise a good introduction to the subject. Even given these caveats, I would still recommend it to any beginning Iranophile wishing to know more about Iran and Iranians.

— Robyn Friend, 1996