New Food of Life: Ancient Persian and Modern Iranian Cooking and Ceremonies

by Najmieh Khalili Batmanglij

Mage Publishers, 2000

(439 pages, with illustrations)

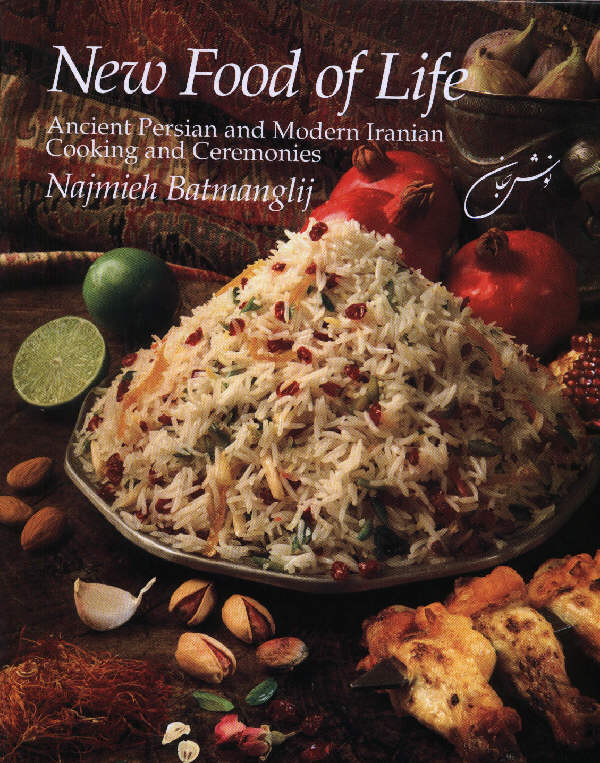

Right from the cover, this looks like a great cookbook: on the front, a mound of Shirin polow, rice with candied orange peel, pistachio, and almond slivers, served with a skewer of grilled chicken; on the back, a charming 19th century oil painting of a Qajar lady in a lovely costume suitable for dancing in.

The promise of the cover is lavishly fulfilled by the contents: hundreds of scrumptious recipes, many for foods I have only had in private homes, and have never seen available in restaurants. Some were entirely new to me (like stuffed potatoes), and some were things that I had previously seen only in grocery stores, but had never known how to make, like kashk (yoghurt cream cheese) and flat breads (lavash, sangak, and barbari). I even learned about a few new things, such as advieh, a spice mix that starts with ground dried rose petals, and includes a different variety of spices depending on the type of food –rice, pickle, or khoresh (stew)– in which the advieh will be used. The absence of this spice mix from my other Iranian cookbooks might explain why my results have never quite tasted like what I have eaten in Iran.

— Robyn Friend, 2001

In addition to the clearly-written and easy-to-follow recipes are a wealth of extras. First of all, absolutely gorgeous photographs of food that are an inspiration to roll up the sleeves and get cooking, or at least to find the nearest Persian restaurant. Which brings me to the section at the back that includes a listing of grocery stores and restaurants that specialize in Persian food, listed by locale, for 23 states, plus the District of Columbia and Canada. Also in the back is a section on traditional Iranian and Muslim ceremonies and festivities, including Now Ruz (New Year’s, celebrated on the vernal equinox), weddings, Ramadan, Ayd-e qorban (Day of Sacrifice), proper tea and coffee making and service, and Shab-e Yalda (celebrated on the winter solstice), all with accompanying illustrations.

Another feature in the back section is a listing of foods with their designation of hot or cold.

People are considered to have “hot” and “cold” natures, as does each type of food. This concept has nothing to do with the temperature or the spice and pepper content of the food; it is a system particular unto itself. For Persians, it is essential for persons with “hot” natures to eat “cold” foods and vice versa, in order to create a balanced diet. [page 419]

In planning a menu one is supposed to consider the “hot-cold” nature of each dish in order to balance each meal. The nature of the food is also supposed to act as a cure for certain conditions, such as eating cold foods when one has a fever, and so on. Some Iranians take this quite seriously; I have actually had a waiter in a restaurant refuse to serve me a particular dish because it would over-balance the menu in favor of the cold, and I had to be content with something else.

The recipes are divided into sections by type: appetizers and side dishes; soups; vegetables; egg dishes; meat dishes; rice; khoresh (stew), and so forth. Each section is introduced by a story or observation about the type of food about to be described, such as occasions when the dish is traditionally served. Scattered throughout the book are reproductions of Persian miniature paintings depicting the enjoyment and preparation of food, as well as little snippets of food-related poetry, in both Persian and English. Stories of the incomparable Mullah Nasruddin, quotations from the Quran, tales from the Shahnameh, and stories from the classical authors add to the beauty of this book, making it not only a book of recipes, but an introduction to the Persian philosophy of food.